Tales From The Passage:

Every stretch of water has two shores, and the only way to reach the second is to leave the first. These notes are for anyone standing on that first shore—pockets light, heart heavier—contemplating if work and wonder can share the same berth.

By Kurt Hunter

THE PASSAGE

Episode 1 — Ketchikan ⟶ Sitka, Summer 1988

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson WilliamsPrologue | Fare North of Free

I had twenty-four dollars in my wallet, which is not enough money to learn any meaningful lessons—unless you gamble it away.

Don’t gamble on the ferry from Prince Rupert to Ketchikan with a gent named Peg in the forward lounge. Money leaves your hand there the way water leaves a glass—quietly, efficiently, and without ceremony. One moment it’s yours, the next it’s memory. By the time the ferry slid into Ketchikan, I was low on funds and lower on dignity, which felt like a fair trade for a story I’d yet to understand.

I washed dishes for a few days to reset the math. Greasy plates, burned coffee, hands pruned from hot water. I stayed at the hostel, the kind of place where everyone is either passing through or hiding out, and sometimes both. At night I made notes—half-sentences, overheard dialogue, nonsense that felt important in the moment. There was a play rattling around in my head, but like most things worth keeping, it refused to sit still.

One evening I found myself in a boat bar called The Crab Pot, nursing something cheap and brown and complaining aloud about my situation, as if the room had asked. The man beside me was a sea-faring type; creased face, salt permanently embedded in the lines of his hands. He listened without interruption, then delivered his verdict with the authority of someone who’d seen too many men argue with gravity.

“Your story,” he said, “is too heavy for a backpack and too light for the ferry fare.”

That felt accurate.

When Captain Lou muttered, “Need hands more than tickets,” I didn’t hesitate. I swapped the price of passage for three days of rope burn, galley duty, and whatever else his sixty-two-foot wooden lady—the M/V Ardent—felt like demanding. Ship hand for hire? Done. Writer on board? Questionable.

The Ardent carried four guest cabins and one fo’c’sle meant for five green crew members who didn’t yet know how green they were. There was also Gunner—a three-legged dog with one good eye and a metronomic tail-thump that served as the ship’s unofficial timekeeper. He kept watch the way only dogs do: without doubt, without expectation, without complaint.

If art is born of constraint, the Ardent was a floating womb.

No privacy.

No money.

No escape.

Just weather, work, salt, and a mind finally quiet enough to listen.

The sea has a way of stripping you down to what you actually carry. And it turned out I’d brought more than I thought—questions, voices, fragments of something unfinished. The kind of cargo that doesn’t show up on a manifest but insists on being delivered all the same.

Day 1 | Ketchikan & Dixon Entrance

0600 — Creek Street drizzle, Ketchikan at it’s finest. Creek Street is cool because it literally cheats geography.

It isn’t a street in the normal sense, but rather a wooden boardwalk bolted onto a cliff, hovering over Ketchikan Creek. No cars. No pavement. Just buildings on time encrusted stilts, hanging above rushing water where salmon still fight their way upstream beneath gift shops and galleries.

But here’s the really great part:

For decades, Creek Street was Ketchikan’s red-light district.

Prostitution was illegal in Alaska, so the brothels exploited a loophole: The “activities” technically took place over water, not land—so the law got fuzzy. The madams ran businesses where customers entered from the boardwalk, but the acts happened above the creek. Bureaucratic shrug. Case closed.

Dolly Arthur—of Dolly’s House—became the most famous madam in Alaska history, running what was essentially a high-end, well-managed operation with strict rules, regular health checks, and zero tolerance for nonsense. She later turned the place into a museum, which is peak Alaska energy: “Yes, this was a brothel. Here’s a souvenir.”

And the anomaly stacks:

🐟 Salmon run under former brothels

🏚️ Buildings cling sideways to a rainforest cliff

🚫 A “street” with no cars

⚖️ A legal gray zone turned cultural landmark

🌧️ Constant rain gives it that wet noir glow

It’s Southeast Alaska in microcosm, improvised, clever, slightly lawless, deeply practical, and quietly poetic.

The tourists were still nursing hangovers when we cast off. I coiled the spring line backward and earned my first glare from Bosun Marlene—sharp enough

to fillet salmon. We nosed north into Clarence Strait, the water iron‑flat, clouds drooping like theatre curtains waiting for their cue.

Passengers

The Rileys — retired schoolteachers photographing every waking moment, including me mopping the head.

Ms. Imani — a birder with binoculars the size of hope.

Jarrett & Cruz — Seattle tech yuppies before the term existed; they brought a fax machine “for emergencies.”

Mrs. Natsukawa — grandmother, never without her sketchbook.

Gunner — honorary guest, paid in jerky. Not so much a guest but treated as such.

1600 — Kasaan Bay

We anchored so the guests could gape at the longhouse poles. My job: shuttle them ashore in the skiff. Gunner insisted on riding bow—ears like prayer flags.

While they toured carvings older than America’s collective memory, I scrubbed kelp from the prop guard and rehearsed a monologue to the gulls. Gunner

offered notes in the form of one decisive bark—better dramaturgy than most grad courses.

Day 2 | Chatham Strait & Peril

0400 — Watch shift

Fog as thick as unspoken love. Radar whispering, bell tolling every two minutes. I poured coffee that tasted of engine oil, counted beats between the swells, and imagined them as drum hits in a song nobody would ever play.

Mid‑morning, the sun broke through—and so did Jarrett’s patience; the fax refused a satellite handshake. He cursed technology, the new sin of Prometheus.

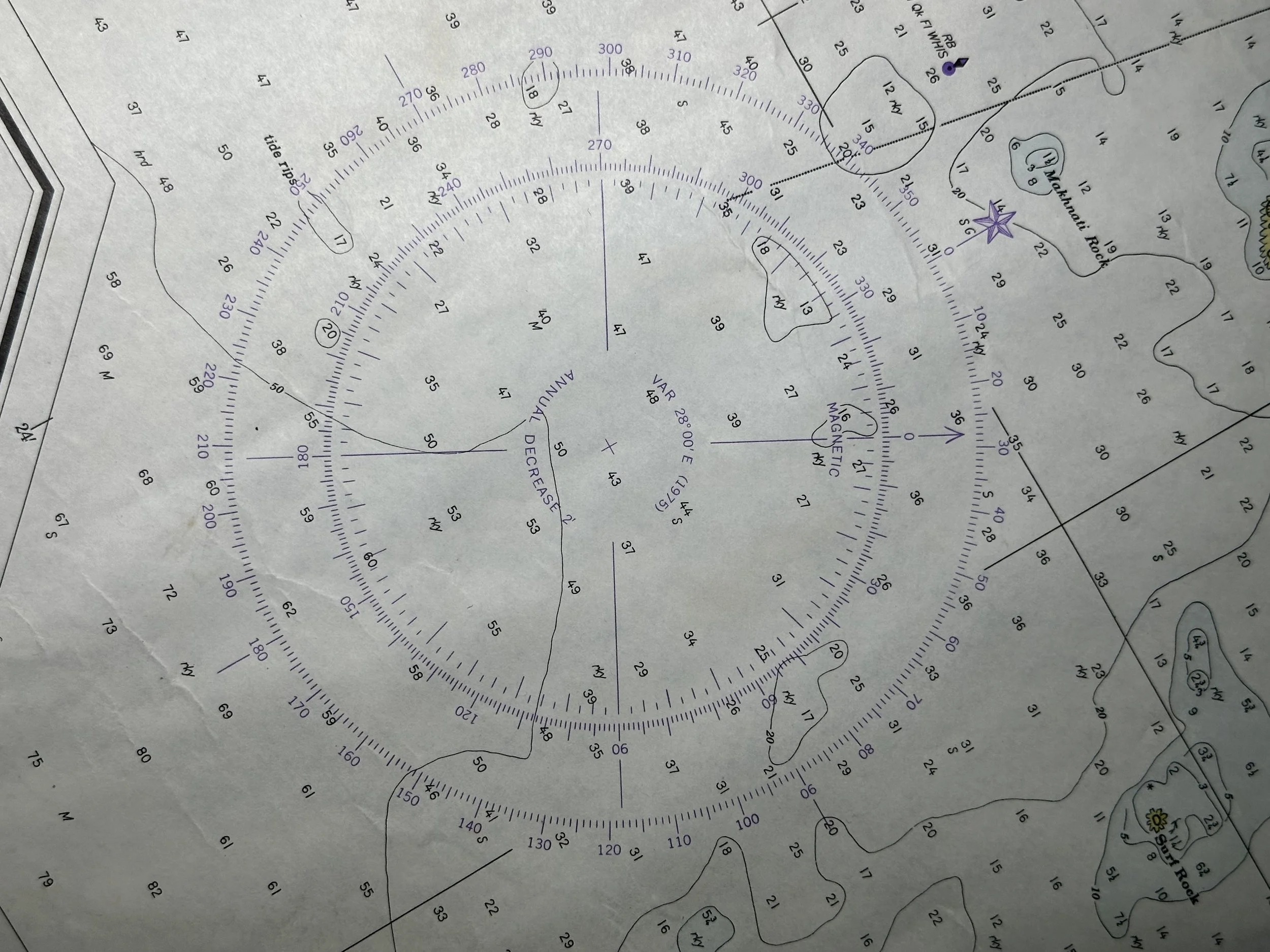

Captain Lou handed him a chart and said, “Try analog.”

Somewhere in that exchange I heard the first chords of a future scene: city boys lost at sea, paper map bleeding in the rain.

Evening — Peril Strait

They don’t call it Peril for laughs. Tidal rapids clutched our keel like a critic hugging an opinion. Bosun Marlene barked orders I only half understood, yet my hands obeyed—line, cleat, line, cleat—until the Ardent slid into calmer water. They say Peril remembers. That it tallies arrogance and impatience, that it measures hulls the way critics measure sentences, looking for weakness, a rushed clause, a boast that doesn’t hold water. Mariners talk about charts and tide tables, but what they mean is respect. You don’t conquer Peril Strait; you negotiate. You show your hands. You keep your mouth shut when the current speaks.

Bosun Marlene finally nodded, a small benediction. The wheel steadied. The engine found its voice again. Somewhere off the port bow, a slick of kelp rolled like a dark thought passing. I wiped my palms on my jacket and felt the aftershock—the clean, electric knowledge that the strait had let us go.

For now.

At supper the captain toasted “safe passes and second chances.” Gunner licked spilled gravy off my boot; I decided that counted as applause.

Day 3 | Salisbury Sound & Sitka

Dawn — Surge Narrows

Amethyst light over Baranof peaks. Ms. Imani spotted a pair of marbled murrelets and swore she could hear their wings whistle. I listened harder and felt

my own pulse sync with the prop wash.

1200 — Approach to Sitka

O’Connell Bridge rose like a proscenium arch. The Rileys cried; Mrs. Natsukawa sketched Gunner poised on the bow—hero of a silent epic.

I hosed salt from the decks, trying to sluice off the feeling that something had shifted inside my rib cage.

Arrival log

Distance: ≈ 300 nm

Coffee pots drained: 9

Lines coiled correctly (eventually): many

New scars: 2 (one knuckle, one idea)

Captain Lou pressed two hundred dollars into my palm—hazard pay, he called it. I tried to refuse; he reminded me the ship ran on barter and kindness.

That night in Sitka I rented a room above the Sheffield Bar, ordered a Rainier, and opened my notebook to a blank page titled “Sawdust Hearts.” The Ardent

horn blew in the distance—another story soon departing.

Somewhere between Ketchikan and Sitka I had traded a ticket for a direction, and perhaps the opening riff of a play that would one day set plywood stages

on fire.

Epilogue | Why The Passage?

Every stretch of water has two shores, and the only way to reach the second is to leave the first. These notes are for anyone standing on that first shore—pockets light, heart heavier—wondering if work and wonder can share the same berth.

Tomorrow the Ardent is slated to nose back out—north through Glacier Bay, then on to Juneau and the ragged rails of Skagway. Captain Lou says there’s an open bunk if "the salt’s still in your veins, kid." It is.

Until the next crossing, E.A.W.

The Fables of Everett Anderson Williams -

Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator - Himself

THE PASSAGE

Episode 2 — Sitka ⟶ Glacier Bay ⟶ Juneau,

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams - Summer 1988

Prelude | Salt in the Veins

Sleep was a rumor. I slipped out of the Pioneer Bar at 0200, my breath ghosting beneath the streetlamps, salt still crystallized on my boots. The Ardent’s mast lights winked from her slip in the channel like a seasoned co‑conspirator. I traced the long Lincoln Street loop around St. Michael’s, paused at the four‑way stop, then wandered up to Castle Hill. A buoy’s foghorn sighed once, and the town settled into a hush—until a raven cut the stillness, begging for either breakfast or to critique my thoughts. The first blade of dawn slid between the mountains and a low‑lurking pressure system. By 0500 I’d collected my backpack and stepped back aboard—pockets lighter, heart fuller in the best possible way.

Captain Lou: “Didn’t think you’d show.” Me: “Couldn’t ignore the rattle in my blood.” Lou (grinning): “Good. Glacier ice’ll cool it.”

New manifest: three days northward, threading narrow passages and unpronounceable bays, finally slipping into Juneau to swap guests and gain provisions.

Day 4 | Sitka Sound & Cross Sound

0600 — Departure Gunner greeted me with a half‑spin, half‑limp, tail whacking the capstan. Clouds piled high like wet cordwood. Bosun Marlene handed me the deck brush in lieu of a welcome.

Crew Additions

Max — college kid on summer break, hired as “science interpreter,” already seasick at the dock.

Chef Lena — took over galley; speaks in haiku and chili‑powder.

1700 — Icy Strait A pod of humpbacks lunged‑fed fifty yards off port. Guests gasped; Captain Lou cut engines. The water rolled like black velvet. I swear I felt the reverberation in my molars—low‑frequency theatre.

Day 5 | Glacier Bay National Park

0800 — Bartlett Cove Rangers boarded to check permits. One, Arliss, carried a carved raven staff and stories older than Shakespeare. He pointed to the forest and said, “Everything you need to know about time is written in the rings.” I pocketed the line.

1200 — Johns Hopkins Inlet We threaded through brash ice the color of candle smoke. Calving thunder cracked the afternoon; each berg rolled like scenery flats changing between acts. Gunner barked at every splash, convinced the glacier was taunting him.

2200 — Lamplight on the Aft Deck Chef Lena passed around mugs of cedar tea. Max, finally upright, charted plankton samples under red light. I jotted dialogue about a man arguing with a glacier—nature heckling hubris.

Day 6 | Lynn Canal & Juneau

0300 — Choke Point

Fuel filter clogged; engine coughed like a veteran smoker. Lou’s knuckles went white on the wrench; Marlene held the flashlight; I prayed to whichever sea god

handles petty mechanical irony. Filter cleared, throttle purred. The night seemed to stretch endlessly, as if reaching into another dimension, even with dawn just an

hour away.

1100 — Approaching Juneau

Rain stitched the water silver. The Mendenhall Glacier glowed blue in the distance, a backstage light behind scrim. Guests crowded the bow; each camera raised

flashed in the mid-morning light.

1400 — Juneau Harbor

Lines fast, engines idle. Gunner disembarked first—business to tend to on shore. Captain Lou slapped my shoulder: “We off‑load, re‑load, and head for Skagway at

first light.”

I nodded, salt still fizzing under my skin.

Log & Lessons

Nautical miles since Sitka: ≈ 220

Icebergs dodged: countless; one kissed the paint

Humpback breaches: 3

Haiku from Chef Lena: 5 (two food‑related, three existential)

New bruises: 1 (fuel hatch argument)

One ranger’s farewell echoed all night: “Glaciers remember what people forget.”

I lay in my bunk composing an answer. Maybe a play isn’t a monument; maybe it’s an echo chamber big enough to keep memory alive.

Tomorrow: Skagway’s ragged rails. And beyond that, who knows—maybe the Yukon if the Ardent keeps tempting me. The salt is still in my veins; the story is still at sea.Until the horizon shifts again,

-E.A.W.

The Fables of Everett Anderson Williams - Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator - Himself

The Passage

Episode 3 — Juneau ⟶ Haines ⟶ Skagway ⟶ Yakutat

The Fables of Everett Anderson Williams - Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator - Himself

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams - Summer 1988

Interlude | Wake Memory

I didn’t grow up on boats. My earliest stages had trapdoors and curtain pulls, not bulkheads and cleats. But

somewhere between missed cues and middling reviews, I started craving something unlit, unscripted.

Theatres and vessels both rely on tension: lines held just tight enough to keep the structure intact. You let one go

slack, and everything starts to drift. When I came to Alaska, I didn’t know whether I was running toward something

or away from everything else—but the ferry from Bellingham to Ketchikan might as well have been crossing oceans.

Captain Lou says you can’t fake being crew. The boat knows. It either folds you in or spits you out. So far, The Ardent is keeping me in the cast. I take that as a sign.

Day 7 | Juneau Turnaround & Lynn Canal

0600 — South Franklin Dock

We off-loaded six very happy passengers, refueled, took on dry goods and six new guests:

A honeymoon couple from Dayton.

A retired hydrologist with a field journal full of doodles.

Twin college photographers with matching windbreakers and completely different attitudes.

A novelist researching a book titled “The Last Frontier (for Real This Time).”

Gunner sniffed them all like a customs officer with a sense of humor.

1000 — Departure

Lines cast. A breeze off the Gastineau Channel made the halyards clatter like backstage chains. I lashed down loose

gear and checked the tension on the skiff hoist—Max had overestimated his knot confidence again. The Ardent

hummed north through gray-green water while Chef Lena recited a breakfast haiku:

Steel gray morning hush

Toast burns, coffee boils over

Storms start small like this.

Day 8 | Haines & Taiya Inlet

0800 — Haines Pier

Mist peeled off the Chilkat Mountains like gauze from a healed wound. We tied up for provisions and dropped mail at

the dock office. Guests wandered into town for souvenir wool and smoked salmon vacuum-packs.

1200 — Battery Point Trail (Shore Leave)

Lou gave me an hour, so I hiked to Battery Point alone. The trees leaned like old actors waiting for their cue. On the

return leg, I sat on a driftwood bench and wrote two pages of a one-act I’ll probably never finish—about a man who

sees ghosts but only on boats.

1800 — Taiya Inlet

We threaded back into the inlet under long streaks of evening light. The water flattened to glass, interrupted only by

diving murres and the ripple of our own reflection.

Day 9 | Skagway & the Red Onion Curtain Call

0700 — Docking in Skagway

Skagway welcomed us with Klondike kitsch and the clatter of the tourist train winding into the hills. I helped secure

the bow line and jumped ashore for errands: propane tanks, ice, and a replacement radio battery that took me into

four different shops and two unrelated arguments about state taxes.

1100 — The Red Onion Saloon

The novelist insisted on visiting. Inside, the bar smelled of old perfume, sawdust, and drama. A woman in corset and

petticoats read off a cocktail list like a casting call. A piano player crooned a ragtime tune while the photographers

snapped photos they’ll never develop. Someone mistook me for a performer. I didn’t correct them.

1700 — Departure

The guests were rosy-cheeked and overfed. I rigged fenders, coiled the aft line twice because I liked the symmetry.

Lou sipped something strong in a tin mug and said, “Next stop, edge of the world.”

Day 10 | Yakutat Bay & Hubbard Glacier

0400 — Graveyard Watch

Fog thick as blackout curtains. The radar blinked like a nervous understudy. I kept my eyes on the green sweep and

listened to the rhythmic thud of waves like the slow count-in before a final scene.

0900 — Approaching Hubbard Glacier

Blue beyond blue, like a shattered stage wall. The ice calved mid-morning with the sound of an orchestra

falling into a pit. Guests gasped. Gunner barked. I imagined the glacier was bowing at the end of an act written over

centuries.

1300 — Yakutat Harbor

We made port under steady drizzle. I helped restock the galley and listened to Max argue with Lena about where

salmon really go to spawn. She won, as usual. That night I slept better than I had in weeks, rocked by the dock and

the knowledge that the journey wasn’t close to over.

Log & Lessons

Nautical miles since Juneau: ≈ 350

New bruises: 2 (winch elbow & coffee spill incident)

Glacier calvings witnessed: 3

Barroom misidentifications: 1

Haiku by Chef Lena: 3 (plus one limerick, unprintable)

Unfinished plays started: 2

Sleep achieved: debatable

One of the photographers asked me, “Do you ever forget you’re on a boat?”

I said, “Only when I’m writing—or when I’m finally starting to feel like I belong here.”

The Ardent pulls out tomorrow for Icy Bay, maybe Cordova. There’s a rumor we’ll pass Elfin Cove. I hope it’s true. It

sounds like a place where you might remember what you forgot to become.

Until the salt recedes,

- E.A.W.

The Passage

Episode 4 — Yakutat ⟶ Icy Bay ⟶ Elfin Cove ⟶ Cordova

Late Summer 1988

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | The Fables of Everett Anderson Williams

Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator – Himself

Let’s admit something upfront: memory, like weather, shifts with pressure. What follows may be wholly factual, or merely

well-rehearsed. Truth in Alaska, like theatre, is less about accuracy than impact. And if I embellish? It’s only because I didn’t

know then that anyone might care to listen now. I’ve sailed a thousand miles on the Ardent, but the greater distance has

been internal. Somewhere between Sitka and Cordova, a question began echoing louder than the boat’s engines: What does

any of this mean? Not just the whales and ice and storms, but my presence in the middle of it all—this accidental odyssey,

cast in a part I never auditioned for.

So this chapter isn’t just a log. It’s a fable, the kind you tell yourself when the shore grows distant and the stars won’t shut up.

But you can’t stop listening.

Day 11 | Yakutat to Icy Bay — “The Drift”

0430 – Departure

Mist hung over the bay like secondhand doubt. Captain Lou, nursing a tin mug and some unspoken history, said only, “Dead

calm. Could go either way.” I took that as both weather report and philosophy.

1100 – Brash Ice, Icy Bay

The bergs here were smaller, fractured like forgotten dialogue. Lena called it “intermission ice,” and we drifted among them

in slow circles, letting the guests take photos and breathe in whatever hush the sea allows.

Max claimed he saw a spirit bear onshore. I didn’t see it, but I believed him—because some stories deserve belief more than

scrutiny.

Interlude | How I Got Here (Part Two)

There was a moment in college when I almost left theatre behind. I’d been cast in a play called “No Exit,” and it felt like truth

—not the text, but the experience: windowless, stifling, recursive. I remember thinking: If I have to keep pretending in rooms

like this, I’ll vanish.

So I took a job painting sets for a touring maritime exhibit. One day, I found myself building a miniature dock for a diorama

of Dutch Harbor. I stared at that tiny ocean and thought, why not the real thing?

The leap from footlights to tide charts isn’t far. Both are ruled by cues and timing. Both reward presence. Both demand that

you pay attention or risk going overboard. And both, if done right, teach you who you are when no one’s watching.

Day 12 | Elfin Cove — “The Monologue”

1500 – Shore Leave

Elfin Cove is barely a whisper between Sitka spruce and tide. A boardwalk replaces Main Street; ravens outnumber people. I

walked it alone, notebook in one hand, a halibut sandwich in the other.

Then, out of nowhere, I met an old fisherman named Abel who recited King Lear like it was scripture. He said the sea helped

him remember lines he'd forgotten when sober. He also claimed he once ferried Edward Albee from Tenakee to Hoonah,

but no one could verify that.

We talked for hours, and at the end he said, “You’re not here to fish or crew. You’re here to remember.”

I didn’t ask what.

Day 13 | Cordova — “Finale in Fog Minor”

0600 – Entering Orca Inlet

Fog hugged the water so close we could’ve kissed it. Marlene steered while Lou charted the narrows. I stood watch, invisible

even to myself. Cordova appeared like a stage set lit from behind—a false town or a real dream.

1400 – Docked at Cordova

Final guest changeover. Lena baked gingerbread for the send-off. The new crowd was louder, brasher, wearing cologne that

made the boat sneeze. I knew I wouldn’t stay aboard. Something had shifted in me—or maybe just settled.

Lou gave me a sideways look and said, “You thinking about jumping ship?”

I nodded.

“Well,” he said, “then you’d better write the next act.”

Log & Lessons

Miles since Yakutat: ≈ 260

Spirit bears spotted: 1 (allegedly)

Shakespeare quotes from strangers: 6

Stories believed: all of them

Goodbyes muttered: too many

Answers found: none

Better questions: a few

Final Entry | On Leaving the Ardent

When I stepped off the Ardent in Cordova, it wasn’t triumph or heartbreak—it was curtain. The kind of ending that feels earned, not resolved.

I still had salt in my veins, but I also had something else: a story. Not finished, but fermenting. The way good ones do. They say a boat stays with you

long after you leave it. So do roles. So do mistakes. So do friends with three legs and cooks who speak in haiku.

I may return. The Ardent sails without me for now, but I left a little piece of myself coiled in her lines. Maybe the next tide will bring me back.

Until then, I’ll write it all down—every wildly unverifiable account.

- Everett Anderson Williams

The Passage

Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator – Himself

Episode 5 — West of the Curtain

Aboard the M/V Harland

Late Autumn, 1988

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson WilliamsPrologue | Why Attu?

Two months since I stepped off the Ardent in Cordova, salt still in my boots and too many goodbyes coiled in my chest. I told myself I’d stick to land for a while—try a stagehand job in Anchorage, finish a draft of Sawdust Hearts/Bleeding Through the Fog, maybe finally call my father back.Instead, I found myself loading crates onto a low-slung supply freighter bound for the far western Aleutians.

The destination: Attu.

A name that doesn’t show up on most maps, but whose silence echoes loud if you know your history.Attu was the site of one of World War II’s most brutal and least-known battles. The only ground combat fought on U.S. soil. Wind-scoured, fog-wrapped, nearly forgotten. And that was the pull.I wasn’t chasing ghosts. Not exactly.

But I wanted to walk a place where the world cracked open and never quite closed again.

And maybe—just maybe—figure out how to write something true about it.Day 1 | Dutch Harbor Departure

0530 – Underway

Boarded the M/V Harland in a sleetstorm, wearing a borrowed parka and the wrong gloves. The crew consisted of:Captain Rhys – Welsh, taciturn, reads Nabokov at the helm.First Mate Sal – chain-smokes and fixes everything with duct tape and a sigh.Cook Milo – former line chef in Barrow. Thinks seasoning is a liberal conspiracy.Deckhands – two. One named Joey. The other doesn’t speak but plays harmonica like a man exorcising his past.

We carry fuel drums, dry goods, medical kits, and a crate labeled SURPLUS / VINTAGE – HANDLE W/ CARE.

I didn’t ask.Interlude | A Scribbled Scene

I started jotting lines again.

Not from the world around me, but from a character I can’t shake:

a young private left behind on Attu after the war ended—

kept alive by habit, birdsong, and the memory of a girl whose name he mispronounced.It’s not a proper play yet. Just side notes scrawled in the margins of Grunge America’s fourth act.

But I think he’s waiting for me out there, somewhere beyond the fog.

So I write to meet him.Day 3 | Adak to Kiska

1000 – Open Water

Swells rise like bad decisions. My bunk feels like a confession booth at sea. Joey claims he saw a submarine off the port bow. Captain Rhys muttered, “Some memories don’t sink.”1700 – Kiska

We anchored offshore. The wind howled through what’s left of the Japanese submarine base—overgrown, rusted, and riddled with Arctic foxes. I hiked partway up the ridge, stepping past old batteries and beer cans from men who came after the war to remember, and stayed just long enough to forget again.Day 4 | Approaching Attu

0400 – Fog Like a Curtain

The radar is our only vision. A wall of vapor so dense it could hide whole empires.

Captain Rhys says Attu only shows itself to the stubborn or the stupid.

I volunteer as both.0800 – Landfall (Barely)

There’s no dock. Just a rusted remnant of pier and a faint trail that disappears into moss and mist.I stepped onto Attu’s shore like entering a hush that had lasted forty-five years.

Nothing moved.

The silence was a sound.I stood at the top of a ridge overlooking Massacre Bay, where the wind made no promises and the earth kept every secret.

I pulled out my notebook and wrote:

This is not a battlefield. It’s a stage, long closed, still echoing the lines.

I don’t know if that makes it sacred or forgotten.And then a thought rose, uninvited but firm:Should I even dare to write about a war I was not a part of?

Should this all be left behind as a warning, or a tragedy?

What right do I have to turn others’ suffering into scenes, or shape memory into metaphor?There were no answers on that ridge.

Only wind.

Only weight.Log & Lessons

Nautical miles traveled: ~1,400

WWII relics encountered: countless

War ghosts confronted: 1 (possibly myself)

Play scenes drafted: 3

Harmonicas heard at sunset: 2

Questions answered: 0

Questions asked: many

Rain: sideways, constant, personal

Final Notes | A Play on the Horizon

Back aboard the Harland, I reread my notes and realized: the soldier I’d been writing wasn’t alone.

He had a radio that never worked.

A crow that visited every morning.

And a memory of theatre back home—one performance he never got to finish.Maybe it’s a ghost story.

Maybe it’s a war play.

Maybe it’s just another wildly unverified account.But I think I’ll call it:West of the Curtain A memory play in one act and many voices.

I don’t know when it’ll be finished.

But I know it began here—

Where the fog writes the opening stage directions,

And the sea holds the last line.— E.A.W.The Passage

Wildly Unverified Accounts from a Semi-Reliable Narrator – Himself

Episode 6 — Driftwood & Memory

Kodiak to Cordova

Early Winter, 1988

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | After Attu

Attu didn’t follow me, not exactly.

But I didn’t leave it behind either.

When the Harland turned east, my body did too—but something in my chest still faced west, like a

weathervane unwilling to yield.

We stopped in Adak for fuel, then hugged the southern coast back toward Kodiak.

I didn’t speak much.

Didn’t write much either, aside from fragments—lines I didn’t understand at the time:

The ocean remembers everything you forget to grieve.

Snow falls sideways on a war that never ended.

A stage, a rifle, a long unanswered call.

Cook Milo asked if I was working on a ghost story.

I said, “Maybe.”

He said, “They’re all ghost stories.”

Day 2 | Kodiak

0730 – Dockside

Stepped off the Harland and onto Kodiak’s cold, wet pavement. There was a coffee shop two blocks inland

where a retired crab fisherman named Cheryl served espresso with a side of local myth. She’d lost three

boats and two husbands, in that order.

She said I looked like I needed a warm drink or a new direction.

I took both.

I wrote for hours in a back booth, sketching the first act of West of the Curtain on a napkin. It starts with wind,

not dialogue. The kind of wind that carries regret across oceans.

Interlude | A Message from the Middle

In the Kodiak public library, I mailed myself a letter:

To E.A.W., wherever he ends up,

Don’t forget the silence on Attu. Don’t rush to fill it.

And if you ever rewrite history, do it with reverence—not ambition.

I haven’t decided if I’ll open it when it arrives.

Day 4 | Onboard the M/V Blue Alder

Captain Rhys found me again. Turns out The Harland wasn’t done with me—just trading cargo for company.

We were headed toward Cordova, with a load of diesel barrels, snowmobile parts, and one cage containing a

goat named Travis.

Same fog. Different ghosts.

Day 5 | At Sea

The sea here is slower. More meditative.

Fewer whales, more seabirds.

I watched a gull ride a thermal like a monologue barely holding its arc.

I think I finally understand what I’ve been doing all these weeks:

chasing fragments.

Grasping for the story between stories.

I’m not here for the war.

I’m here for what remains in the silence after it ends.

For the characters left off stage.

For the driftwood stories.

Day 6 | Cordova Arrival

1330 – Dock Ties Fast

Cordova: muddy boots, rusted trucks, and seagulls with opinions.

I stayed at a fisherman's hostel where someone played blues guitar until 2 a.m.

I dreamed of a stage set adrift on the ocean—planks held together by barnacles and hope. No audience.

No curtain. Just wind, lines whispered to the waves.

Log & Lessons

New nautical miles: ~500

Coffee cups consumed: 9

Napkins turned into scenes: 4

Goats encountered: 1

Personal ghosts: quiet (for now)

Letter to self: mailed, unopened

Next heading: uncertain

Final Notes | A Play, Maybe

West of the Curtain continues to unfold like sea charts I haven’t yet learned to read. I don’t know where it’s

going—but I know it needs to be told.

Not to dramatize suffering. But to catch its echo.

To remind us what silence can say.

Tomorrow I’ll try to find work on another vessel.

Someplace new.

Someplace quieter.

Because the salt hasn’t left me.

And the passage isn’t over.

— E.A.W.

The Passage

Episode 7 — The Sound of Returning

Cordova → Juneau → Sitka → Ketchikan

Early Winter, 1988 - A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | The Ardent Returns or The Pier Where Things Begin Again

Cordova Harbor in early winter smells like rust, diesel, and frozen halibut.

I’d been killing time on borrowed boots and less borrowed thoughts—waiting for something to pull me forward again.I didn’t plan it.

I never do.And then, like a line tossed from a dream:

The M/V Ardent.Tied up at dock seven, salt-streaked and barnacle-kissed. Her running lights dim, but steady. A ship that remembers you even when you’ve forgotten yourself.I hadn’t seen her since Glacier Bay in late summer.She looked older, but so did I. And somehow more real.It was like bumping into a childhood friend after the funeral of someone you both once loved.Day 0 | Return Without Ceremony

I didn’t approach right away.Not because I was nervous, but because I wasn’t sure I was allowed to feel what I felt.I stood across the harbor road drinking a watery coffee, watching the crew offload crates of root vegetables and mail sacks. I saw Clyde—still limping, still talking to himself. A new deckhand I didn’t recognize was hosing down fish bins. No Gunner. Maybe retired. Or moved ashore.Marlene spotted me first.

Still in her orange slicker, still barking orders, still slicing through deck chaos like a blade through sea foam.

She paused mid-coil and gave me a nod that doubled as both greeting and job interview.And then:

Captain Lou, descending the wheelhouse steps like it was still July. A bit grayer. A bit slower. But unmistakable.He looked over once and nodded like we were in mid-conversation.The snow let up. The water stilled.Captain Lou didn’t ask where I’d been.

He just said:“We’re down a man. You still know how to coil a line?”I said, “Better than I know what day it is.”He grinned.Five minutes later, I was on the manifest again.Captain Lou: “Sitka run—then down to Ketchikan if the weather holds. You know the drill.”Me: “Do I ever not?”The story—whatever it had become—had circled back to page one.Same play.Different act.Day 1 | Below Deck, Above the Past

The crew bunk still smelled like cedar and diesel.

I found a pair of gloves I’d left in July. They hadn’t moved.

Neither had the ache in my ribs from where I slipped hauling a crab pot that summer.The Ardent wasn’t just a boat.She was a reminder that the world was wide and stitched together by water.

That movement could be a kind of healing.

That some stages float.Diesel and salt | Back Where I Belong, For Now

There’s a sound a boat makes when you step aboard again after time away.

It’s not the creak of the deck or the snap of the lines.

It’s subtler.

Like a sigh. Or a welcome. Or maybe your own heartbeat slowing to meet the rhythm you forgot you loved.The Ardent didn’t ask where I’d gone or what I’d learned.

She just floated there, steady as memory.And so I’m back—

Not as a lost man,

But as one who's still listening.The Passage continues.

Because home, it seems, isn’t a place.

It’s a vessel that waits.I fell asleep to the hum of the generator, lulled not by exhaustion, but belonging.We departed Cordova before dawn.

Guests aboard: six.Including an older couple from Seattle, two biology grad students from Boise, and a divorced commercial fisherman named Buck.And one unexpected spark.Interlude | The Guest with the Smile

Her name was Eliza, mid-thirties, traveling with her mother as a kind of post-divorce reset.She wore a dark green wool coat and read Joan Didion on the foredeck, hair tied up, eyes wary but curious.We met during a supply handoff in Valdez.

She handed me a thermos of coffee with a raised eyebrow and said,"You look like someone with a lot of thoughts and no one to tell them to."I said, "That’s why I became a playwright."She laughed.And for three days, we spoke in fragments—little exchanges over railing views and shared glances in the galley.A kindness of timing. Nothing expected. Everything noticed.Day 3 | Juneau

By the time we reached Juneau, snow was falling sideways.Marlene and I offloaded two pallets of dry goods.Captain Lou refueled.I ducked into a bookstore on Franklin Street and found a dog-eared copy of Death of a Salesman.I opened to the middle and scribbled a line from Grunge America in the margin:“It’s not that the dream died—it’s that no one paid the cover charge to keep it alive.”I hadn’t touched the script in weeks. But here, on this trip, something stirred.

A vision of that stage that has yet to happen, and how it will break every rule.Punk chords. Chain link fencing.The American flag, spray-painted and torn.Dialogue like drum fills.Monologues shouted over distortion pedals.People called it chaotic.Some said it was sacred.All I know is, it mattered.Maybe it still does.Day 4 | Sitka Sound

We slid into Sitka Harbor under low fog and creaking winch lines.The same town where this whole thing started for me, months ago.Eliza and I walked the shoreline after dinner, boots crunching frost and silence between us.She said she was flying home from Ketchikan, but wasn’t in a rush.That night, while the rest of the boat slept, she knocked on the galley door with two mugs of tea and a question:"What’s the play you’re not writing?"I didn’t answer.

But I kissed her.

Not because I had answers.

But because some moments deserve punctuation.Day 5 | Ketchikan Arrival

The trip ended like most voyages do: with the quiet chaos of departure.

Luggage thumped. Radios squawked. Paperwork rustled.Eliza squeezed my hand. No promises.Just an understanding.She boarded a seaplane.I stayed aboard the Ardent, helping Marlene inventory rope and gasket seals.Captain Lou tossed me an oil-stained rag and said:

“You off again? Or sticking around this time?”I looked at the dock. The mountains.

And the sea that still had more to say.“Let’s see what the next tide brings.”Log & Lessons

Miles traveled: 630Pages added to Grunge America (Redux): 12Kisses: 1Regrets: 0Coffee thermoses shared: 3Number of plays not being written: at least 2Number of plays becoming something else entirely: maybe 1Stage directions for life: TBD

Final Notes | A Stage Still Afloat

The Ardent has never felt more like home.

Not because it’s comfortable.

But because it keeps you honest. Keeps you moving.

Eliza left with a line of mine in her notebook.

I stayed with one of hers in my mind:

“What’s the play you’re not writing?”

Maybe I’ll find it.

Or maybe I’ll live it.

Either way, the passage continues.

— E.A.W. The Passage

Episode 8 — Northbound Echoes

Ketchikan → Prince Rupert → Beyond

Late Spring, 1989

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | The Next Tide

I stayed with The Ardent, stayed with Marlene’s steady sarcasm, stayed with Lou’s gruff silences and moments of questionably factual stories. Stayed with the sea.

And yet, something had shifted.

The pages I’d scribbled for Turn of a new decade rattled in my duffel like loose bolts.

Every line demanded more.

Maybe that’s what Eliza left me:

permission to begin.

Day 1 | South from Ketchikan

Guests disembarked, new ones boarded. Families with too much luggage, a fisherman’s widow with none.

Marlene caught me staring at the dock where Eliza’s plane had gone.

Marlene: “You look like someone left the stove on.”

Me: “Maybe I did.”

Marlene: “Then best to keep moving. Sea doesn’t wait.”

By noon, we were threading Tongass Narrows, the gulls heckling us like unpaid critics.

Day 2 | Quiet Miles

The weather turned, drizzle soft as stage fog. I found myself back in the galley during downtime, washing mugs, humming under my breath.

Not sea shanties.

Not hymns.

Journey.

“Don’t Stop Believin’,” had a beat that kept up a dialogue.

Words rose with it. The dialogue fragments came to me in a sea chanty written by a disgruntled Republican in Reagan’s cabinet. Stupidly honest and unapologetic.

For the first time, I thought: this play I had in mind might actually work.

Day 3 | Prince Rupert

We tied up for supplies. I walked into town, carrying a dog-eared copy of the draft.

At a café by the tracks, I ordered weak coffee and mailed a packet south. Not to an agent, not to a theatre. To Eliza.

Inside the envelope:

The new draft.

A single note: “You asked what I wasn’t writing. Here it is. Don’t let me off easy.”

The clerk weighed it, stamped it, tossed it in the bin.

It felt like a curtain had risen, even if no one was watching.

Day 4 | Back Aboard

That night in the crew mess, Lou grunted over the charts.

Lou: “So what now, Williams? You staying with the sea, or chasing words?”

Me: “Maybe both.”

Marlene: “God help us. He’ll be writing stage directions for the bilge pumps.”

Laughter. Small, but real.

Log & Lessons

Miles logged since Ketchikan: 220

Draft pages mailed: 1 packet, fragile contents

Cups washed: ~40

Songs hummed: 3 (all out of tune)

Moments of doubt: too many

Moments of resolve: one, but it mattered

Final Notes | Northbound Echoes

I don’t know if Eliza will ever write back.

I don’t know if Turn of a new decade will ever leave the page.

But I know this:

Every tide carries you somewhere new.

Every voice—whether from a jukebox, a crewmate, or your own stubborn pen—can be a compass.

And maybe the only way forward is to keep writing, keep sailing, and keep believing.

The passage continues.

Northbound. Southbound. Always somewhere.

— E.A.W.

The Passage: Episode 8½ — Notes from the Galley

Interior: Train galley. Late. The car hums like a distant dream. Everett wipes down a cutting board, stacks steel bowls with a little too much precision. Outside, snow blurs the landscape. Whitehorse is still ahead. He hums the “Porkchop Express” theme quietly under his breath. Then, his voice—steady, wry, tired—comes in like a remembered journal entry.

EVERETT (V.O.):

There’s a kind of loneliness to scrubbing dishes in motion.

You move forward, but your mind drifts back.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about playwrights.

beat

Not the gods, not the geniuses. The rest of us. The ones dragging words across the page like nets behind boats, hoping something worth keeping shows up.

I wrote a list once, on a napkin in Prince Rupert.

It started like this:

(He recites from memory. Dry. Knowing.)

1. Self-centered narcissists.

2. Studied at a school with a name but never studied people.

3. Get stuck on themes like gum on a boot.

4. Write about places they’ve only read about.

5. Think every play needs a love triangle or a gun.

6. Mistake “clever” for “true.”

7. Use the stage to preach instead of ask.

8. Every character is just them in a hat.

9. Cast for girlfriends.

10. Did I mention narcissists?

He chuckles, gently shaking his head.

It’s not fair, maybe.

But I’ve met most of them.

Hell, I’ve been most of them—on the wrong nights.

beat

But there’s another list. One I don’t talk about as much.

Wrote this one in a hotel room in Haines, right after Cindy’s monologue clicked.

(This time his tone softens, almost reverent.)

1. They listen. Not just to dialogue, but to silence.

2. They’ve been broke, and they know how to make do.

3. They make a town feel like a living character.

4. They trust a pause.

5. They rewrite like they’re digging for water.

6. They steal from life without leaving bruises.

7. They’re not afraid of being disliked.

8. They can make you laugh while your chest aches.

9. They write people, not arguments.

10. They tell the truth—the deep, messy, recognizable kind.

Everett sets down the sponge. Wipes his hands slowly.

EVERETT (V.O.):

I think this play started because I got tired of pretending I wasn’t scared of being ordinary.

Because even if no one reads it...

Even if Eliza never writes back...

At least I said what I meant.

He reaches into his duffel, pulls out another dog-eared copy of the play. Holds it like something breakable. Then places it into an envelope already addressed.

EVERETT (V.O.):

One more copy into the world.

Another paper boat in the river.

Fade out on the train disappearing into the frozen dark, lights dimmed, snow chasing the rails.

Here's Episode 9 of The Passage, titled “North by Northwest”, as he trades tides for train tracks, maritime memories for the steady hum of wheels through boreal wilderness. He doesn’t know why he’s going to Whitehorse—only that something’s pulling him there. Maybe it’s the rhythm. Maybe it’s the silence. Maybe it’s the echo of something he hasn’t written yet.

The Passage

Episode 9 — North by Northwest

Prince Rupert → Whitehorse

Late Fall, 1989

A deckhand’s diary (or train jockey) by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | Goodbye to Salt

There was no ceremony when I left the Ardent.

No final toast. No dramatic line.

Just a shared nod with Marlene as she coiled line for the next voyage.

Captain Lou didn’t even turn from the helm.

I disembarked in Prince Rupert with a duffel, a half-finished play, and the smell of diesel still folded in my jacket.

I’d been on the water for months.

I loved it.

But the tide inside me had changed.

It wasn’t wanderlust exactly.

It was more like a question I didn’t yet know how to ask.

So I turned inland.

Day 2 | Railways & Rituals

I found work washing dishes in the narrow galley car of a Canadian National railliner—cutlery clattering like jazz as the Rockies unspooled outside.

My bunk was thin.

My pay was thinner.

But the movement felt familiar.

The head cook, Garvey, had two rules:

Never burn the bacon.

Always hum something while drying.

So I hummed.

Mostly movie themes.

Sometimes fragments of half-written monologues.

And more than once, the Porkchop Express theme from Big Trouble in Little China—that synthy, off-kilter anthem of ridiculous swagger and unexpected heroism.

Garvey asked if I was a musician.

I said, “Something like that.”

Day 3 | Somewhere Near Fraser Lake

The pine trees blurred by like forgotten names.

I started writing again.

Not Grunge America (Redux).

Something else.

A character named Jasper, riding westward to escape a memory that keeps showing up in bus stations and shoe stores.

I don’t know who Jasper is yet.

But he talks like a man who’s been underwater too long.

Maybe he’s me.

Maybe not.

I wrote the first scene on the back of an old Canadian Tire receipt:

Lights up on a train. Empty except for a man holding a photo. He’s humming, not a song, but the echo of one. He looks out the window and says: “Even the trees are running from something.”

Day 4 | Whitehorse Arrival

We rolled into Whitehorse under a sky that looked brushed in graphite.

Snow on the rails.

Coffee on my sleeve.

Mind racing.

I stepped off the train and didn’t know where to go.

So I didn’t.

I just stood there.

Breathing.

A woman passed me on the platform and said, “You look like someone who followed an idea too far and got exactly where he needed to be.”

I said, “You might be right.”

She smiled.

Walked on.

Interlude | The Northern Quiet

I found a bunk at a small hostel above a hardware store.

In the common room, someone was playing Leonard Cohen through dusty speakers.

I pulled out my notebook and jotted a single sentence:

The story isn’t what happens. It’s what lingers after.

That night, I dreamed I was performing on a frozen lake.

No stage. No lights.

Just an audience of elk.

And I didn’t know my lines.

But no one seemed to mind.

Log & Lessons

Dishes washed: ~350

Tips received: 2 (both in the form of songs)

Train miles traveled: ~950

New characters invented: 1

Plays completed: 0

Questions answered: none

But something feels closer.

Final Notes | The Road Still Unfolds

Whitehorse isn’t where this ends.

But it might be where something begins.

There’s talk of a road north—to Dawson, to Inuvik.

Or maybe I’ll find a theater here.

A pub stage.

A chorus line of frostbitten monologues.

For now, I’m staying still.

Not because I’m tired,

But because sometimes, the play begins only when the curtain doesn’t rise.

The passage continues.

Even if I’ve traded waves for wheels.

— E.A.W.

This is a pivotal moment in The Passage, when Everett Anderson Williams stops drifting and feels. When the sea of movement he’s been floating on pulls him inward, and what he finds there is the first raw seed of Grunge America—not yet fully formed, but trembling with urgency, aching to be written.

Here is:

The Passage

Episode 10 — Tuesday’s Gone

Whitehorse, Yukon Territory

Winter, 1989

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | What Breaks Through

It wasn’t dramatic.

It wasn’t theatrical.

There were no voices from God, no signs in the sky, no muse in red lipstick.

Just a small room.

Old wallpaper.

A beat up tape deck on the windowsill.

And a song.

I was supposed to be looking for work.

Maybe find a stagehand gig or something with the CBC.

But the cold had pushed me inward.

And a man can only spend so many nights writing bad monologues before he cracks or curls up.

So I laid back on the bed.

Put on a cassette someone left behind in the hostel swap bin.

And as “Tuesday’s Gone” came on, slow and sad and sure, something… loosened.

Interlude | The Moment Before the Word

There was this line in the song:

"Train roll on, many miles from my home…"

And suddenly I wasn’t in Whitehorse anymore.

I was in every bus station I’d ever passed through.

Every loading dock I’d slept on.

Every theater that closed too soon.

Every friend I’d left behind.

Every version of myself I thought I’d outgrown.

I felt like a kid again.

Not in the good way.

In the aching, “what-the-hell-happened-to-us?” kind of way.

And I cried.

Quietly.

No sobbing. No howling.

Just a steady, necessary release. Like fog lifting.

The Scribbled Beginning

I pulled out my notebook.

The one I always said was for "ideas," but mostly used to sketch half-finished maps and draw seagulls.

I wrote:

ACT I, Scene I — A boy with no name in a flannel shirt stares into a broken TV in the corner of a laundromat. A sign reads: “No soap, no hope.” Outside, someone is spray-painting the word DREAM across the wall of a pawn shop.

Soundtrack: Mudhoney, early.

Lighting: fluorescent and unforgiving.

Tone: raw, unfiltered, American as a wound.

And it kept coming.

Characters, places, rhythms.

Cindy with her bleached hair and sticker-covered guitar.

Jace, the ex-Marine who now teaches poetry and sells pills.

The manager of the 24-hour convenience store who swears he's seen angels on the roof during lightning storms.

Every line was a question we forgot to ask in the ‘80s.

Every beat a reminder that change doesn't come like a parade—it comes like a cough in the middle of a love song.

Log & Lessons

Hours since I pressed play: ~6

Pages written: 17

Title circled in thick black ink: GRUNGE AMERICA

Notes in the margin: “Tone = rage + tenderness + confusion”

Number of plays I’ll write after this: Who knows

Number of selves I had to lose to write it: at least two

Is Tuesday gone? Maybe. But something stayed.

Final Notes | A Play, A Prayer

It’s not done.

Not even close.

But something opened.

I didn’t try to write about America.

I tried to write about me, and I ended up with all of it.

The flannel. The fear. The fire inside people who’ve been told they’re too angry or too loud or too off-key.

And I’ll be damned if that’s not America in 1990.

A scream under the static.

A heart still beating under piles of VHS tapes and broken walkmans.

Grunge America isn’t a title.

It’s a dare.

And I just took it.

— E.A.W.

The Passage

Episode 11 — The Bar Reading

Whitehorse, Yukon Territory

Late Winter, 1990

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | Paper, Pride, and Proof

It was a cold Tuesday, but the bar was warm and close, thick with boots on floorboards and breath fogging the glass.

No name on the door—just “OPEN” in faded red vinyl, and a laminated sign that read: NO COUNTRY ON THE JUKEBOX AFTER 8PM.

I’d been nursing a half-shot of Yukon Jack and the courage it promised for forty-five minutes. I tossed down another, reached into my coat, and pulled out the first quarter-draft of Grunge America—twenty-four pages of rage and reverence, heartbreak and grit.

Not perfect.

Not polished.

But if I didn’t let it out tonight, I never would.

Scene | The Bell and the Dare

I stood up, tapped a bar spoon against a pint glass.

Three people turned. One muttered, “Here we go.”

Me: “I’m a playwright. Sort of. I’ve got a new piece, and it’s not ready for critics. But it’s ready for ears.”

A pause. One booed, affectionately. A regular.

Me: “If you read it—if you read it right, with some honesty, no speed-reading, no sloppy bullshit—I’ll ring the bell and buy the whole room a round.”

A guy by the dartboard: “What’s it about?”

Me: “It’s about America. The one nobody writes about unless they’re blaming it for something. It’s about kids who grew up watching the world break in high fidelity. It’s about stolen guitars, scratchy couches, and wanting something more than survival.”

That got murmurs. Curiosity.

I handed out the pages. One set per person. No extras.

Cadence & the Cue

I walked over to the jukebox.

Hit B-17. 5 times.

Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

The piano started—slow, spaced, open.

I turned to them.

Me: “Follow that beat. Feel it. Let the words ride it. This isn’t Shakespeare. This is a kid watching a Clash poster curl off the wall. This is someone screaming into a vent fan at their Circle K job.”

THE SETTING: A bus stop turned American wasteland

The scene takes place at what is technically a bus stop but symbolically, it’s America in transition,

America in decline,

America in denial,

America waiting for a bus that never comes.

Linny, a truck dispatcher with a voice like gravel and smoke, started as Cindy. She didn’t act. She just was.

Cindy (Linny’s voice):

“They told us the future was waiting, but it looked just like the past. All gray and chewing on us. The ’80s were all shine, no shelter. You wanna know what’s left? A bill we can’t pay and a hunger that doesn’t quit.”

A silence, then she went on, slower, sharper.

Cindy:

“Middle class, lower class; what’s the difference when both are sinking? My mom works two jobs. My dad works none. And me? I work at not becoming them.”

The bar hushed.

Even the dartboard stopped.

She finished with a few lines that hit harder.

Cindy:

“They want us to be the status quo. Be our parents. Be quiet. Fold our dreams like towels and stack them in a linen closet for a house we’ll never own. They want 1984 haircuts and 1984 obedience, smile for the church directory, clap for the flag, pretend trickle-down ever trickled. But I remember who did the trickling. Reagan crafted it and I remember Gordon telling us greed was a virtue. That shit hollowed whole neighborhoods and called it prosperity.

So no—I’m not going back. I’m not putting on their good-girl cardigan and marrying a mortgage. I would rather scream myself voiceless on a basement rock show where the drywall peels and the amps buzz than sit at their nice oak table and thank them for a future I don’t want.

Call it rebellion, call it ungrateful, call it whatever makes you sleep. I call it survival! We’re not rerunning their decade. We’re the generation that saw the rot under the red, white, and blue bunting, and we’re done taking instructions from people who confused cruelty for strength.”

The Room Holds Its Breath

Jace’s lines came next. They were read by a logger with knuckles busted from winter work. His soft tenor gave the ex-Marine’s words a strange gentleness.

Jace:

“They told us the fight was over, but the war followed me into laundromats and empty kitchens. I see it in the humming lights, in the sound a fridge makes when it forgets what it’s holding. Peace was just a sentence they read to keep us quiet while the same men signed the same papers with the same pens. They patched bodies, not the wound. They sent us home to sit to in fluorescent rooms, hope for help and called it victory. That’s the part that breaks me—how a whole country can clap for an ending it never bothered to make real. That’s the betrayal—finding out the system survived the war better than we did.”

Punctuated by a pool cue slapping against the painted cement bar floor.

“Sorry”, a Vet at the tables said, quietly.

Jace:

“They told me I fought for freedom, but all I came home to was a stack of bills and a country too busy buying answers to ask the right questions.”

It’s short, guttural, and bitter, but still lyrical enough to echo.

For 20 minutes and 55 seconds the bar leaned in. 8 voices, reading multiple lines of dialogue, an act and a half following the story leading up to the midpoint.

Not magic.

But something close.

The Bell

When the last page fell quiet, and Journey faded out for the 5th time, I walked to the bar.

Said nothing.

Rang the brass bell so hard the bartender jumped.

Me: “First round’s mine. You all gave me something I couldn’t do alone.”

They cheered. Not wildly—just with the kind of warmth that meant they’d heard me. That meant it mattered.

Log & Lessons

Pages read: 30

Glasses raised: ~18

Lines flubbed: 3

Lines that landed: too many to count

Journey track: played to the end

Bartender’s verdict: “Not bad, playwright. Next one’s on the house if it’s about this bar.”

Final Notes | Echoes

Back in my bunk, I found a note tucked into my notebook. From Linny.

“Don’t let anyone rewrite her. Cindy’s all of us. Don’t make her soft. Make her survive.”

I taped it to the inside cover.

Poured another half-shot.

Some nights, you speak.

Some nights, the world answers back.

And some nights—like this—you realize the play isn’t a product.

It’s a pulse.

— E.A.W.

The Passage

Episode 12 — A Re-Entry Into Chaos

Whitehorse → Portland, Oregon - February 1990

A deckhand’s diary by Everett Anderson Williams

Prologue | The Number That Shouldn’t Have Traveled

Whitehorse had a stillness that could swallow a man whole.

Snowbanks leaning against buildings like exhausted drunks.

Phone booths standing like monuments to lonelier decades.

I should’ve known better than to give out the greasy spoon’s number—the one I’d scribbled on a napkin and told a friend back in Seattle:

“If anyone needs me, call here. I’m working mornings until I get paid.”

A mistake.

Numbers migrate.

And bad news migrates faster.

The cook—Ronny with the nicotine mustache—held the receiver up toward me like it was a dead fish.

“Some guy’s cryin’ your name through the line,” he said.

“Sounds like a country song without the charm.”

I took the phone.

A beat.

Breathing that sounded like someone trying too hard to sound in danger.

“E? It’s Markus. I’m… I’m in trouble, man.”

Markus. Christ.

The only man alive who could turn an overdue electric bill into Greek tragedy.

His voice trembled—but that was his voice even on good days.

Every syllable a plea, every story a performance.

“What kind of trouble?”

“…It’s—hard to explain. Just come down. I need you. You’re the only smartass I trust.”

I felt the cynicism rising like bile.

If trouble was real, he’d have details.

If trouble had a creator, he would possess an excessive amount of intricate information.

He had none.

But it gnawed at me anyway.

Not loyalty—God no.

Curiosity.

The ugly kind.

The kind that ruins vacations and derails lives.

Maybe this was my re-entry trajectory—my drop back into the Lower 48, into the world I kept orbiting but never committing to.

A return to gravity after too much time floating north of it.

I told him I’d be there in 5–6 days.

I wasn’t sure I meant it.

Day 1-2 | Train Out of Whitehorse

Trains out of the Yukon don’t glide; they grind.

The wheels scream.

The passengers don’t.

My seatmate ate sunflower seeds like he was angry at them. Across from me sat a man reading Atlas Shrugged with the desperation of someone hoping it would teach him how to be important. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that book saved no one.

The car smelled like diesel, wet wool, and regret. Not a luxurious combination, but honest.

I stared out the window and thought about trouble.

Trouble has a tone.

A posture.

A humidity.

Mark’s trouble had none of these things.

I wrote in my notebook:

“Some men create emergencies so they don’t have to confront the quiet.”

A line for Jace, maybe.

Or maybe for me.

“America is a place where the trains run on time only when no one needs them to.”

Seeds. Lines. The beginnings of something.

Something jagged.

Day 3 | Washington by Bus

Crossing the border was uneventful.

The border agent asked where I was going.

I said “Portland.”

He asked why.

I said, “Bad decisions.”

He didn’t laugh.

Which made me laugh.

I transferred to a bus headed toward Yakima. A kid behind me blasted a tinny cassette of Mudhoney. Somewhere between the chords I started hearing the shape of Grunge America.

Not the plot.

Not the characters.

The tone.

A country hollowed out by its own promises.

Bus seats have a way of reminding you you’re mortal.

Springs, foam, vinyl—all conspiring against the human spine.

In Washington, the rain felt like an old friend who never apologized for being late.

Raw.

Unstable.

Like someone recorded it while escaping a burning building.

It rattled something in me.

Something old.

Something angry.

Day 4 | Hitchhiking the Dead Middle

The bus broke down near Goldendale.

The driver blamed the snow.

The snow blamed the bus.

I started walking.

Thumb out.

Head down.

That kind of day.

My rides were America in miniature:

Ride 1: a logger who hadn’t slept in two days.

Ride 2: a woman escaping a husband who “found Jesus but lost perspective.”

Ride 3: a silent rancher who gave me half a turkey sandwich without a word.

All of them lost.

All of them moving.

The national pastime.

America, in pieces.

America, honest.

By sundown I was in The Dalles, staring at the Columbia River like it owed me rent.

I scribbled:

“The 80s sold us a dream. The 90s want their damn money back.”

Day 5 | Portland Arrival

I stepped off the last ride under the Burnside Bridge.

The Willamette smelled like wet pennies and bad decisions.

I called M.

No answer.

Typical.

I found a cheap room off Stark Street where the clerk looked like he’d been embalmed prematurely.

I was exhausted, so I took a nap.

Portland in February is a wet postcard someone left in their jeans through the wash cycle.

Smudged.

Damp.

Shrugging off its own myth of weirdness.

I called Markus, again.

The line rang.

And rang.

And rang.

Trouble doesn’t avoid people.

It clings to them.

So whatever this was—it wasn’t trouble.

It was a man reaching for a lifeline he had no intention of grabbing.

I slept with my boots on.

Habit.

Or readiness.

Or both.

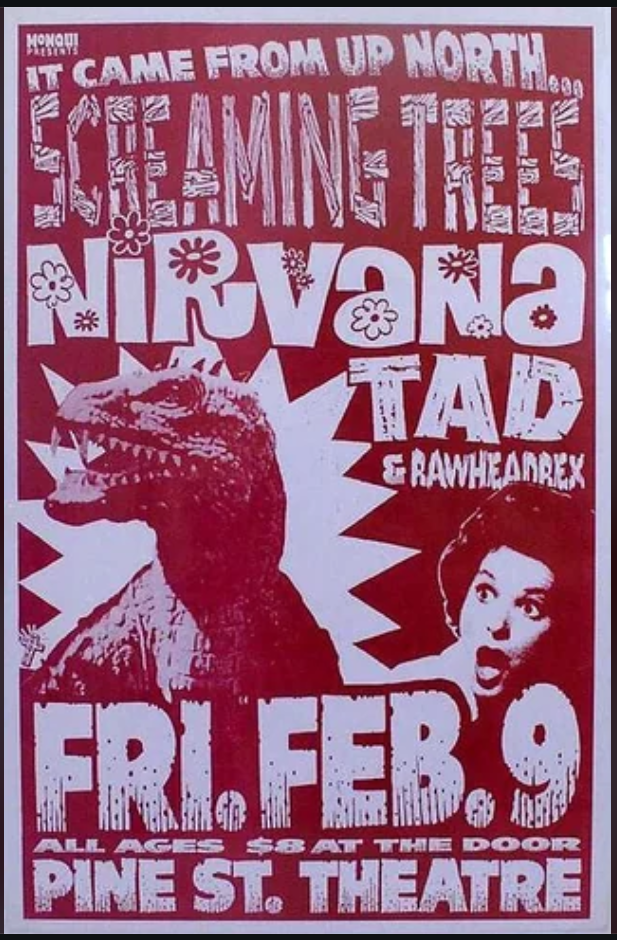

On a power pole out front was stapled a show flyer for Nirvana, playing the Pine Street Theater—Feb. 9, 1990.

Five bucks at the door.

Three if you looked poor enough.

Day 6 | Pine Street Theater

M. still missing.

His “trouble” still undefined.

His note still smelling like manipulation.

But Portland had other plans for me that night.

Inside the Pine Street, the floor smelled like beer, sweat, and history.

At the lobby bar getting a beer, I heard, “Don’t Stop Believing’,” slow and steady against the clink of enamel cups. I followed the beat the way I’d told the bar crowd to weeks earlier.

I wandered into the theater and found my seat, thinking the bar that night, the dialogue fragments. Half-monologues. Cindy, Jace, the unnamed boy in flannel—they came alive again, clearer than before.

Then the first guitar chord hit and my ribcage vibrated like it had been waiting for this frequency since childhood.

Kurt snarled into the microphone like the world had betrayed him personally.

And we, the crowd, believed it.

They played School. And when the first distorted chord from hit,

I felt something tear open.

Not pain.

Not nostalgia.

Recognition.

Here it was:

The sound of a generation too tired to scream and too furious not to.

The sound of a promise breaking in real time.

The sound of kids who saw through the patriotic gloss and corporate rot and said the quiet part loud.

No polish.

No glamour.

Just truth with amps.

I wrote the line on my wrist in ballpoint pen so I wouldn’t forget:

“America doesn’t need heroes. It needs witnesses.”

That was it.

That was the spine.

Grunge America was no longer a scattered draft—it was a live wire.

Kurt Cobain leaned into the mic, almost swallowing it, and yelled:

“NO RECESS!”

And the crowd erupted, a collective exorcism of everything we were promised but never given.

I finally understood what I’d been trying to write.

Not a play.

A cultural autopsy.

A battle hymn.

A truth serum delivered through distortion.

LONG LIVE distortion.

LONG LIVE truth.

LONG LIVE the sound that saves you because nothing else will.

And somewhere in the middle of that hurricane, the truth arrived:

THIS was what the 1990’s were going to be.

Not hope.

Not rebirth.

Not the shiny New America the Reagan ads promised.

But rage.

And distortion.

And disillusionment braided into power.

I wrote on my forearm in ballpoint ink:

“America doesn’t need heroes. It needs witnesses.”

The crowd screamed.

I screamed with them.

Not to join—

but to purge.

This wasn’t a concert.

This was a cultural autopsy.

And Grunge America—the thing I’d been writing around instead of writing—

suddenly had a heartbeat.

Raw.

Loud.

Unapologetic.

Long live distortion.

Long live truth.

Long live the voice that cuts through the bullshit with three chords and enough pain to power a small city.

I left the theatre knowing exactly what I needed to write.

Markus could wait.

Final Notes | A Shift in Orbit

No sign of Markus.

No explanation.

Not even a call.

But maybe he wasn’t the one who needed help.

Maybe I was.

And maybe the help came wrapped in flannel, distortion pedals, and a scream that said:

“We’re fucked, but we’re not lying about it.”

The Passage continues.

Not north.

Not south.

But dead center into the wound.

— E.A.W.